「山の寄り合い」が描いた新しい知の風景|New Landscapes of Knowledge from Yoriai On The Hill

オランダからゲストを招き、読書会、模合、鯰絵、干支について議論したWORKSIGHT最新号。そこから見つめ直した、異なる知のあり方とは。Based on discussions on themes such as Dokushokai, Moai, Namazu-e, and the Eto, the Dutch guest reconsidered new ways of knowing.

大阪・関西万博に参加中のオランダは、パビリオンを飛び出し、日本各地でさまざまな対話・協働を行う「文化プログラム」(Dutch Cultural Program)を開催している。WORKSIGHTもそのプログラムの一環としてコラボレーションを実施した。

2025年5月、編集部はオランダからのゲストと、日本の研究者、編集者、デザイナーらを集め、栃木県さくら市喜連川のお丸山ホテルを会場に1泊2日のスタディキャンプ(合宿)を開催。そのディスカッションの様子を一冊丸ごと使ってドキュメントする特別号『WORKSIGHT[ワークサイト]28号 山の寄り合い Yoriai On The Hill』を制作した。

スタディキャンプのテーマは「Ideas from Asian Vernacular」。日本のさまざまな民俗を紹介し、国籍や立場を超えて議論することで、これからのわたしたちがどのように集まり、どう対話することができるのかを考えることを狙いとした。具体的な題材は4つ。江戸時代に立場を超えた討論空間を生んだ「読書会」、現在も沖縄に深く根付く金融と相互扶助が一体となった仕組みである「模合」、江戸末期に地震災害を多層的に捉えた「鯰絵」、干支の循環する時間がつくる人のつながりの一例である「生年祝い」だ。

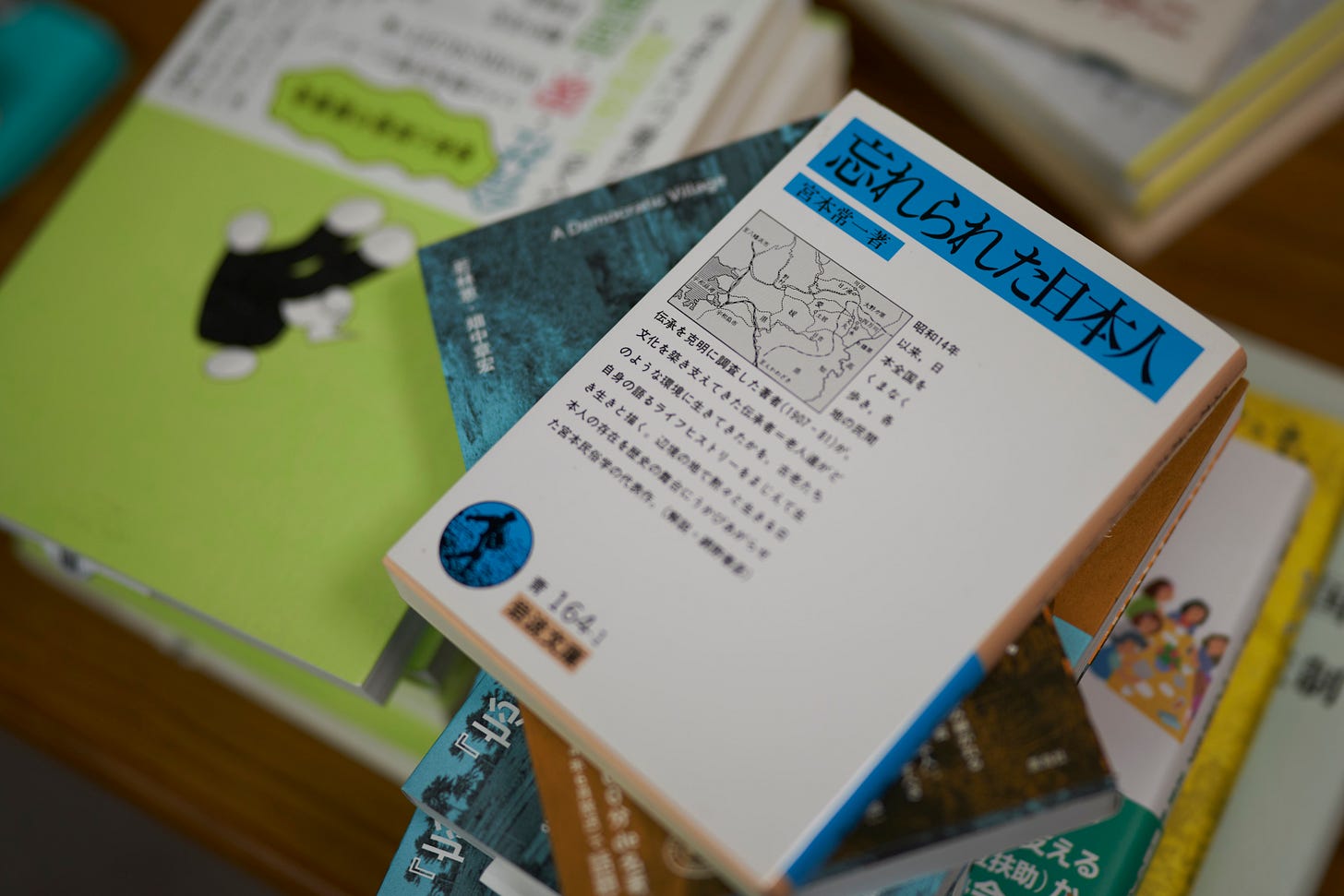

参加者たちは結論の出ないテーマに対して、休み時間や食事の間もぐるぐると話を行い、それぞれの体験を共有していった。それはまるで民俗学者・宮本常一が名著『忘れられた日本人』に記した「寄りあい」のような場所となった。

WORKSIGHT28号では「寄り合いを終えて」と題して、参加者それぞれに合宿の振り返りを依頼した。すると、オランダの「文化プログラム」全体のファシリテーションを行うStudio The Future共同ディレクターのヴィンセント・スキッパーから、誌面の枠を大幅に上回る熱のこもった原稿が送られてきた。本誌では泣く泣く抜粋版の掲載となってしまった彼のメッセージを、今回のニュースレターで全文掲載し、お届けする。

The Netherlands, currently participating in Expo 2025 Osaka Kansai, has stepped outside its pavilion to organize the Dutch Cultural Program, a series of dialogues and collaborations held across Japan. As part of this program, WORKSIGHT also carried out a collaboration.

In May 2025, the editorial team hosted a two-day study camp in Sakura City, Tochigi Prefecture, at the Omaruyama Hotel in Kitsuregawa, bringing together guests from the Netherlands alongside Japanese researchers, editors, and designers. From these discussions, we produced a special issue, WORKSIGHT Vol. 28: Yoriai On The Hill, which devotes an entire volume to documenting the exchange.

The theme of the study camp was Ideas from Asian Vernacular. By introducing various Japanese folk practices and engaging in discussions that transcended nationality and profession, the aim was to explore how we might gather and converse in the future.

Four specific topics were chosen: the reading circles (Dokusyokai) of the Edo period, which created spaces for debate across social positions; Moai, the system of finance and mutual aid still deeply rooted in Okinawa; Namazu-E, the disaster prints that depicted earthquakes in layered ways at the end of the Edo period; and Seinen-Iwai, a communal celebration tied to the cyclical flow of the Eto (zodiac).

The participants continued their conversations even during breaks and meals, sharing their experiences in response to themes with no fixed conclusions. It became a space much like the yoriai described by folklorist Tsuneichi Miyamoto in his classic The Forgotten Japanese.

In WORKSIGHT Vol. 28, under the title Yoriai and Beyond, each participant was invited to reflect on the camp. Among the responses, Vincent Schipper—Co-Director of Studio The Future and facilitator of the Dutch Cultural Program as a whole—sent us a passionate piece of writing that far exceeded the space available in print.

While the magazine could only carry a condensed excerpt, we are now publishing his message in full here in this newsletter.

photographs by Yasuhide Kuge

text by Vincent Schipper

ヴィンセント・スキッパー アムステルダムを拠点に活動するアーティストユニット/デザインスタジオ/出版社「Studio The Future」共同ディレクター。日本での各種リサーチ、フィールドワークも数多く行う。日本語が堪能で、日本通。今回のオランダ文化プログラム全体のファシリテーションも担っている。

Vincent Schipper Co-director of Studio The Future, an artist collective, design studio, and publishing house based in Amsterdam. Has conducted extensive research and fieldwork in Japan. Fluent in Japanese and deeply knowledgeable about Japanese culture. Serves as the facilitator for the entire Dutch cultural program.

もうひとつの知

合宿を振り返ると、わたしが考えていたのは日本とオランダの違いでも、「東洋」と「西洋」の対比でもなく、むしろ現代の世界を支配している思考の流れそのものについてだった。ヨーロッパ的な文脈が、世界中に覆いかぶさるように拡張され、固有性や地域性を抑圧し(正統性を奪い)、結果として「もうひとつの知」の可能性そのものが閉ざされている。そんな感覚だ。

この支配は、その内容というよりもむしろ「形式」にはっきりと見えてくる。知がどのように構造化され、獲得され、正当なものとされるのか。そのあり方だ。読書会や模合、鯰絵についての議論を通して、かつて知に至る道がいかに多様であったか、そしていまもそうであるべきかを強く思い起こした。だがその多様性は、いわば思考の「科学化」と呼ぶべきものによって徐々に削がれてきた。啓蒙主義によって形式化され、産業革命によって硬化し、中立や進歩という名目のもと世界中に輸出された世界観である。

現代の高等教育制度は、こうした「知をひとつの型に押し込める仕組み」の最も目立つ遺産だ。そこでは特定の正典や方法論だけでなく、知がどう生まれ、どう正しいと認められるか、その決定権までも制度化してしまった。その支配力はあまりに強大で、批判する人までもがその論理に縛られてしまうほどだ。そこには「正しい」知の獲得方法があり、物語より引用、経験よりデータ、参加より論文発表が重視される。何を学ぶかだけでなく、どう考えるかまでが規定されている。矛盾したり、心変わりしたり、「知らない」と認めたりすることは、いまやタブーとされている。というのも、わたしたちが生きている制度のなかでは、それらは「機能不全」や「役に立たないもの」と見なされてしまうからだ。

上:ホテル周辺を散歩する「寄り合い」の参加者たち。喜連川塩谷氏が築城した大蔵ヶ崎城跡が「お丸山公園」として整備されている

下:散歩中のヴィンセント・スキッパー(中央)と、メディア「One World」にて編集長を務めるサアダ・ノールハッセン(左)、オランダ文化プログラムにサポートとして参加する編集者/ディレクター・黒木晃(右)

Top: Participants of the yoriai gathering take a walk around the hotel grounds. The site of Okuragasaki Castle—originally built by the Kitsuregawa-Shioya clan—has been developed into what is now Omaruyama Park

Bottom: Vincent Skipper (center) on a walk, together with Seada Nourhussen (left), editor-in-chief of the media platform One World, and Akira Kuroki (right), an editor/director participating in the Dutch cultural program as support

大学の歴史的役割から、わたしたちはどれほど遠く離れてしまったのだろう。かつて大学は、開かれた対話や共同の思考、知恵の追求を行う場として構想されていたはずだ。それがいまや職業訓練の場へと変貌している。カリキュラムは「有用性」、つまり就職に直結すること、経済需要に応じることを軸に設計されている。こうした転換は探求の幅を狭めただけでなく、既存の権威をいっそう固定化し、生産性こそが正統性であり、価値は常に測定可能でなければならないという観念を強化してしまった。その結果、スローで、推測的で、直観的で、共同的な知のあり方は正統性を奪われてきた。生産性は本来、人間の尺度ではなく、世代を超える長い時間軸で考えるべきものだ。だが現在は、短期的投資と即時的リターンにすり替えられてしまっている。ではいったい、何が「生産的」であるかを決めているのは誰なのだろうか。

本質的には、それは権威の問題だ。この問いは学問領域を超えて、社会のあり方全般に影響している。政策の決定、専門性の定義、正統性の付与にまで及ぶ。その帰結は単なる知の単一化ではなく、想像力の政治的な極度の縮減にほかならない。

ここでわたしは、長くミラノのカトリック大学で教えながら、その思想ゆえに静かに解任されたイタリアの哲学者、エマヌエーレ・セヴェリーノを思い出す。彼は西洋形而上学の根幹を問い直し、現代を支える虚無的論理を批判した。わたしにとって『The Essence of Nihilism』(虚無の本質)は、内容すべてに賛同するからではなく、西洋思想に深く埋め込まれ名指しすらされない前提をあえて揺さぶるからこそ、重要な書であり続けている。

わたしたちは、もはや見えなくなったものを名指すことが難しい。だがまさにそれこそが停滞の核心だと思う。世界は知のあり方において徹底的に一元化されてしまったのだ。それでも幸運にもしぶとく残り続ける場所がある。思考や組織づくり、知の分かち合いといったものの別のあり方が、かろうじて保たれている小さな領域が。そこはユートピアではない。脆く、ときに矛盾し、危うさをはらんでもいる。だがそれでも、知や理解、そして経験をさらに広げていくために、欠かすことのできない場なのだ。

栃木県にあるお丸山公園から見下ろした喜連川の町

The town of Kitsuregawa as seen from Omaruyama Park

「世界の終わりを想像する方が、資本主義の終わりを想像するよりも容易である」ということばをよく引用する。フレドリック・ジェイムソン、スラヴォイ・ジジェク、あるいはマーク・フィッシャー……誰が最初に言ったかはさておき、その指摘は確かだ。わたしたちはイデオロギー的な閉塞のただなかに生きている。地球の破壊でさえ、このシステムの解体より想像しやすい。資本主義とは経済モデルにとどまらず、現実そのものを縁取る装置となっている。

あらゆる枠がそうであるように、それは排除を伴う。成長を前提としない社会のあり方を排除し、貨幣に還元できない価値の理解を排除し、そして「イノベーション」や「進歩」という枠組みに収まらない知をも排除する。その結果、わたしたちは衰退を批判し、分析し、記録することはできても、それ以外を想像することはほとんどできなくなっている。喪失しているのは生態系や社会だけでなく、想像力そのものなのだ。

その最も危険な物語のひとつは「前進」の神話だ。歴史は直線的に進み、新しいものは常に古いものより優れており、技術革新は人類の進歩と同義だとする考え方。この信念体系はあまりに根深く、疑問を呈されることもない。だがそれこそが、最も有害な制度を支えている。収奪的な経済、植民地主義的イデオロギー、教育の序列、そして何よりも現状に甘んじる態度だ。

だからこそわたしは、寄り合いの議論を必要なものだと感じた。それは壮大な代案を提示するのではなく、ただ立ち止まり、別の可能性を思い出させてくれる契機だった。知は口承であり、共同的であり、消えていくものでもいい。対話はゆるやかで、循環的で、結論に至らなくてもいい。知識は資格からではなく、経験から生まれることもある。生産的でなくとも、それには意味と目的がある。

議論を通じてわたしは、「ともに問い、矛盾を抱える」ことの必要性を再認識した。近代が要請する、効率化や最適化、明確化といったものに抗う形式を大切にする必要がある。むしろ曖昧さや混沌、未解決をこそ受け入れるのだ。

今日失われつつあるのは、物語の豊かさだけではなく、知のあり方そのものだ。ホラーは未知と共にあることを教えてくれる。それは単なる娯楽ではない。なぜなら、恐怖を解消せずに名指すことを可能にし、情動的で、身体的で、深く社会的な知を伝える形式だからだ。

だから「Ideas from Asian Vanacular」というこのプロジェクトのタイトルを考えるとき、わたしは地理を思い浮かべない。そこで考えるのは姿勢だ。水平的に学び、異なる者同士が統合を求めずに語り合い、矛盾や沈黙や緩慢さを許容するという態度だ。

もっとも、それと同時にわたしはノスタルジーの罠に陥りたくはない。失われた共同体の知恵や前近代的な調和を夢見るのではない。文明の純粋性や地域の優越を唱えるナショナリズムを信じるのでもない。歴史が繰り返し示しているのは、知が常に「旅」をしてきたことだ。文化とは常に開放的で、動的で、相互に関わり合ってきた。交易の道も、語り継がれた物語も、人びとの移動も、すべてが交わりながら、知の風景を描いてきた。

わたしが信じているのは、知を組織し、語り、伝えるこうした形式を改めて参照し直す必要があるということだ。それを琥珀のなかに封じ込めるためではなく、わたしたち自身を形づくるために。いまのシステムが必然ではないことを思い出すために。そして、わたしたちの対話のかたちは、わたしたち自身の手で組み直せるのだと気づくために。

寄り合いという形式は、完璧ではなくとも、その可能性を見せてくれた。わたしたちが集ったのは成果のためではなく、ともに引き受けるという姿勢のためだった。耳を傾け、問いかけ、声に出して考えるということ。その姿勢こそが寄り合いの核心なのだ。

Knowledge Otherwise

In reflecting, I find myself returning not so much to the contrast between Japan and the Netherlands, or between "East" and "West," but rather to the hold certain streams of thought have over much of our contemporary world. The particularly European context has, to a great extent, been overlaid across the globe, suppressing (delegitimizing) specificity and locality in ways that fundamentally obstruct the possibility of knowledge otherwise.

This hold becomes most visible not through its content but through its form: the way in which knowledge is structured, attained, and legitimized. Throughout our conversations—in our sessions on kaidoku, moai, and namazu-e—I was reminded of how radically plural the paths to knowledge once were, and still ought to be. Plurality has been steadily diminished by what might be called the scientification of thought, a worldview which was formalized through the European Enlightenment, hardened by the Industrial Revolution, and exported globally under the guise of neutrality and progress.

The modern tertiary education system is one of the most visible legacies of this epistemological enclosure: an institutional form that promotes not only a specific canon or methodology, but also a specific authority over how knowledge is produced and validated. It is a system so dominant that even its critics often remain bound by its logic. There is now a “correct” way to come to knowledge—one that favors citation over storytelling, data over experience, publication over participation. This is not just a matter of what we study, but how we are allowed to think. Contradiction, changing one’s mind, or admitting not knowing have become taboo — more because they are deemed within the systems we now operate in as dysfunctional or lacking in utility.

合宿中に使用した参考書籍

Reference books used during the retreat sessions

What’s particularly striking is how far we’ve drifted from the university’s historical role. Once envisioned as a place for open-ended conversation, collective reasoning, and the pursuit of wisdom (in its totality), the university has become increasingly vocational. Curricula are now designed around what is “useful,” what leads to employment, what aligns with economic demand. This shift has not only narrowed the scope of inquiry but has further entrenched existing systems of authority, reinforcing the idea that legitimacy lies in productivity and that value must always be measurable. In doing so, it has delegitimized other ways of knowing—those that are slow, speculative, intuitive, or collective. Now it is about productivity on a human scale, but if you consider it but when considered on a global or epistemic scale, knowledge unfolds over spans far beyond years or even generations. Today, productivity is no longer about the future, but about short-term investment and immediate return. But who, then, determines what is—or isn’t—productive?

It’s in essence a matter of authority. This question echoes far beyond the walls of academia and extends into how society functions at large: how policy is made, how expertise is defined, how legitimacy is awarded. The result is not just intellectual monoculture, but a deeply political narrowing of our imagination.

I’m reminded here of the work of Emanuele Severino, the Italian philosopher who for years taught at the Catholic University of Milan until he was quietly dismissed for his ideas. Severino questioned the very foundations of Western metaphysics and what he saw as the nihilistic logic underpinning modernity. His book The Essence of Nihilism has long been formative for me, not because I agree with every page, but because it dares to interrogate the assumptions so deeply embedded in Western thought that they often go unnamed.

It’s difficult to name what we no longer see. And that, I think, is at the heart of the miasma. The world has been extensively singularized in terms of knowledge: how it is pursued, presented, and discussed. Luckily, there remain holdouts—pockets of perseverance, places where other ways of thinking, organizing, and sharing knowledge still exist, however tenuously. These are not utopias. They are fragile, sometimes even contradictory, and sometimes dangerous — but they are a necessity for the development and further expansion of knowledge, knowing and experience.

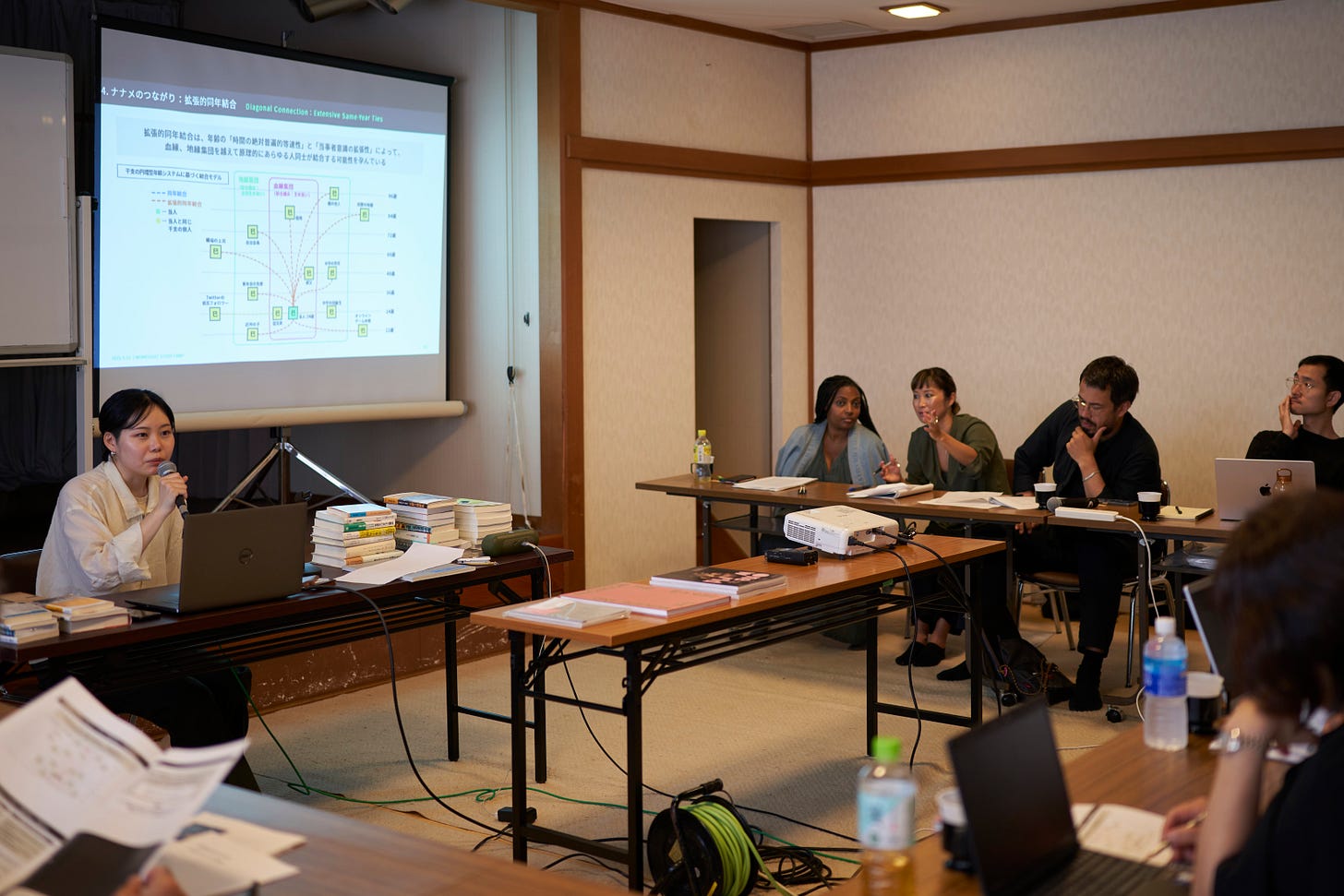

合宿中のセッションの様子

Scenes from the retreat sessions

This brings me to a quote often misattributed but nonetheless powerful: "It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism." Whether it was Fredric Jameson, Slavoj Žižek, or Mark Fisher who first said it, the point stands. We live in a state of ideological closure, a form of realism so total that even the destruction of the planet is easier to conceive than the dismantling of the system doing the destroying. Capitalism, in this context, is not just an economic model. It is a frame for reality itself.

And like any frame, it excludes. It excludes ways of organizing society that are not growth-oriented. It excludes understandings of value that are not monetary. And crucially, it excludes knowledge that does not fit into its model of "innovation" or "progress." The result is a world in which we can critique, analyze, and document our decline, but rarely feel capable of imagining anything else. The loss, then, is not only ecological or social, it is imaginative.

One of the most dangerous narratives we have inherited is the myth of forward motion—the idea that history moves in a straight line, that the new is inherently better than the old, that technological advancement is synonymous with human progress. This belief system is so embedded that it often goes unchallenged. And yet, it underpins some of our most harmful systems: extractive economies, colonial ideologies, even educational hierarchies, and, most insidiously, complacency.

This is why I found the Yoriai discussions so necessary. They weren’t offering alternatives in the grand, utopian sense. Rather, they offered a chance to pause and remember that alternatives exist. That knowledge can be oral, communal, ephemeral. That discussion can be slow, circular, unresolved. That knowledge can emerge from experience, not credentials. Even though they might not be “productive” they have sense, they have meaning, and thus also purpose.

The discussions reminded me of the need for acts of shared curiosity, contradiction, gestures that embrace uncertainty. There is a need to take care of forms that resist the modern imperative to streamline, to optimize, to clarify. They invite us instead into the murky, the messy, the unresolved.

What gets lost today is not just narrative richness, but an entire epistemic mode. Horror teaches us to sit with the unknown — it is not merely entertainment. To name our fears without resolving them. To pass on knowledge that is emotional, embodied, and deeply social.

And so, when I reflect on the "Asian vernacular" invoked by the title of this project, I don’t think of geography. I think of attitude. A willingness to learn horizontally. To speak across difference without the demand for synthesis. To allow for contradiction, silence, and slowness.

I also don’t wish to fall into the trap of nostalgia. I don’t long for some lost era of communal wisdom or premodern harmony. Nor do I believe in nativist fantasies that posit civilizational purity or local superiority. History shows us, again and again, that knowledge travels. That cultures have always been porous, dynamic, interconnected. Trade routes, storytelling traditions, migratory movements—all have played a role in shaping how we know.

What I do believe is that we need to revisit these ways of organizing, discussing, and transmitting knowledge. Not to preserve them in amber, but to let them shape us. To let them remind us that we have a choice. That the systems we live under are not inevitable. That the architecture of our conversations is ours to redesign.

Yoriai, as a format, offered a glimpse of what that could look like, though not perfect, it invited us to gather not around an outcome, but around a commitment. A commitment to listen, to ask, to think aloud.

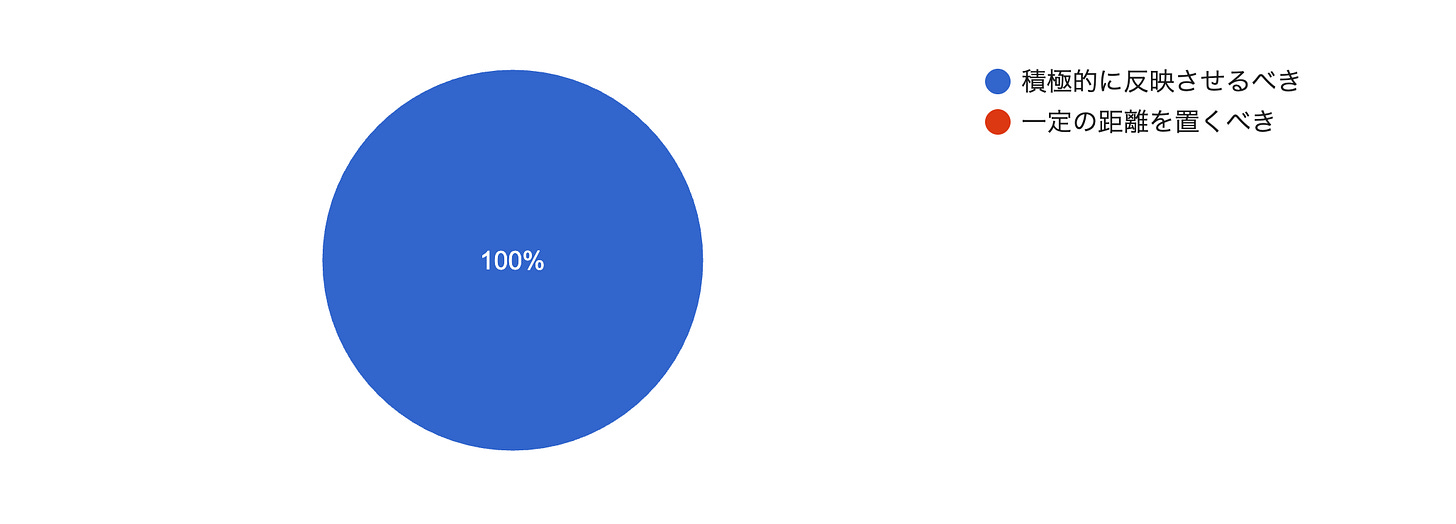

【WORKSIGHT SURVEY #18】

Q:現代に「寄り合い」があったとしたら?

宮本常一の著作『忘れられた日本人』によると、村の寄り合いには議題やアジェンダがなく、雑談のようなゆるゆるとしたやり取りが三日三晩も続いたといいます。もし現代の生活において、こうした「寄り合い」という合議の方法が身近にあったとしたら、あなたは参加してみたいと思いますか? みなさんのご意見をお聞かせください。

Q:What if we had “Yoriai” today?

According to folklorist Tsuneichi Miyamoto’s book “The Forgotten Japanese,” the traditional village yoriai had no set agenda. Instead, loose, almost casual conversations went on for as long as three days and nights. If such a way of collective deliberation as yoriai were part of our daily lives today, would you want to take part in it? We’d love to hear your thoughts.

【WORKSIGHT SURVEY #17】アンケート結果

美的なだけがデザインじゃない:韓国のスタジオ「日常の実践」が向き合う政治と社会(8月26日配信)

Q:デザインは、もっと政治的・社会的な「時代の声」を反映すべき?

【積極的に反映させるべき】デザインは非言語的なシステムとして活動できると考えるから。

【積極的に反映させるべき】昔も今も、アートやデザインで政治主張をすることは、表現のひとつとして重要な手段だと思っています。

【積極的に反映させるべき】デザインには、良くも悪くも世論をつくる力があるため、その力を世界がより良くなる方向へ使ってほしいと思います。

次週9月9日は、2025年6月29日~7月4日にかけて黒鳥社が主催した「ANOTHER REAL WORLD Shanghai/Shenzhen DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE TOUR 2025」の振り返りレポートを配信。なぜ中国ではデジタル・イノベーションが次々と生まれるのか。『アフターデジタル』シリーズで知られる株式会社ビービット日本リージョン代表・藤井保文さんとともに、その理由を考えます。お楽しみに。

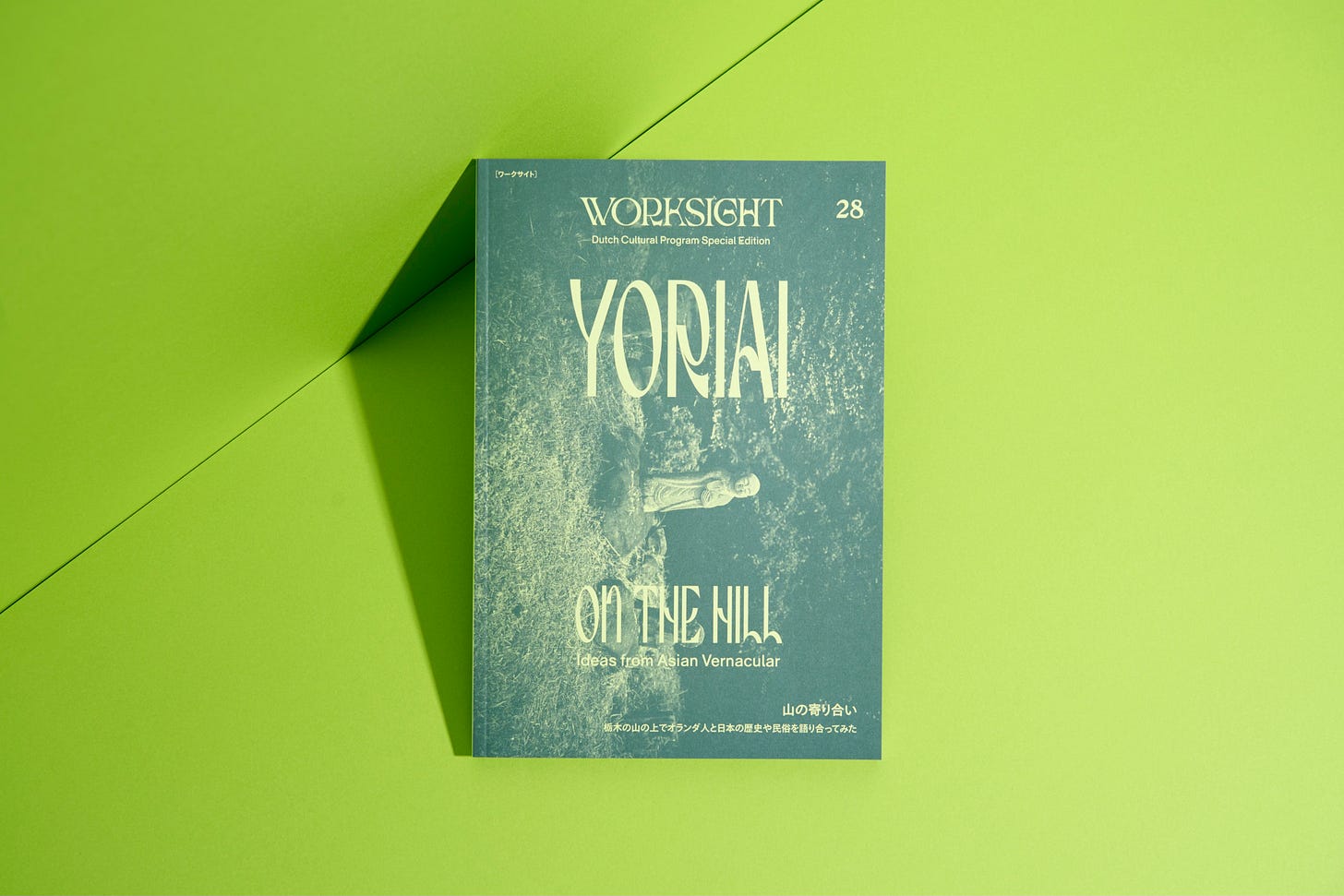

【新刊案内】

photograph by Hironori Kim

書籍『WORKSIGHT[ワークサイト]28号 山の寄り合い Yoriai On The Hill』

その日、日本思想史家や文化人類学者、民俗学者、採集家、写真家、ウェブデザイナーらが、栃木県のとある山上の宿に集った。村の寄り合い、江戸時代の読書会、鯰絵、沖縄の模合や生年祝いなど、アジアに息づくオルタナティブな合意形成の実例を手がかりに、オランダの人たちとともに分断の時代における新しい「協働のかたち」を探った交流合宿。その模様を一冊にまとめた、オランダ文化プログラムとのコラボレーションによる特別編集号。

書名:『WORKSIGHT[ワークサイト]28号 山の寄り合い Yoriai On The Hill』

編集:WORKSIGHT編集部(ヨコク研究所+黒鳥社)

ISBN:978-4-7615-0935-4

アートディレクション:藤田裕美(FUJITA LLC)

発行日:2025年8月26日(火)

発行:コクヨ株式会社

発売:株式会社学芸出版社

協力:Nieuwe Instituut、お丸山ホテル

判型:A5変型/128頁

定価:1800円+税